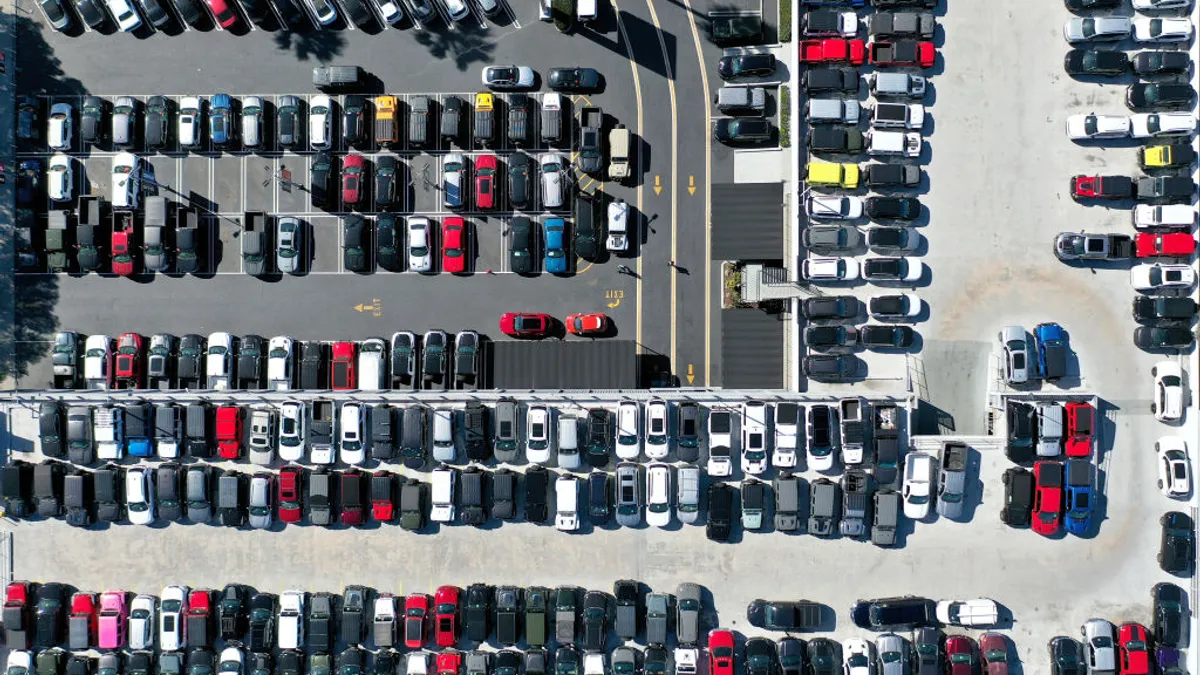

As new vehicle inventories in the U.S. stabilize near a targeted average supply of 60-80 days, automakers must ensure their product mix meets consumer demand, experts told Automotive Dive.

That could prove difficult amid uncertainty over federal support for electric vehicles as Republicans take power in Washington and consumers grapple with affordability woes.

“The devil’s task right now is to be a product planner,” said Erin Keating, executive analyst and senior director of economic and industry insights at Cox Automotive. “Figuring out the right mix of powertrain distribution will be their main struggle.”

Although new vehicle inventories are healthy at 85 days’ supply, EV inventories remain significantly higher compared to internal-combustion-engine vehicles, despite larger incentives on these models, according to Cox Automotive. In September, EV inventories were 91 days’ supply, while ICE vehicles were 79 days’ supply, according to Cox Automotive.

Additionally, even though new vehicle affordability is improving, automakers still need to lower prices because a lack of used inventory makes it difficult for many would-be buyers to get into a vehicle.

“A lot of consumers that would normally buy a three- or four-year-old vehicle are now buying six-, seven- or eight-year-old vehicles,” said Tyson Jominy, vice president of data and analytics at J.D. Power.

Cutting production is usually better than slashing prices

The auto industry often relies on incentives to help clear inventory by making vehicles more affordable for consumers, spurring additional sales.

New vehicle incentives during Q3 reached 7.7% of the average transaction price, increasing more than 60% year-over-year, according to Cox Automotive. However, incentives remain significantly below pre-pandemic levels, which often exceeded 10% before COVID struck, according to Kelley Blue Book.

OEMs are increasing incentives slowly to safeguard their profit margins, while dealers are discounting more and earning lower profits, Jominy said. It’s an about-face from 2022 when dealers earned record profits by selling vehicles above MSRP because they could raise prices faster than manufacturers.

Lowering production is often a better alternative to consumer incentives because it lowers dealer floor planning costs and allows automakers to maintain or even raise their prices, experts said.

“When an automaker’s inventory gets high, the answer isn’t just to put cash on the hood,” said Stephanie Brinley, principal automotive analyst at S&P Global Mobility. “Tighter inventory is financially better for everyone.”

Automakers adjust vehicle production per model to ensure their inventory mix matches consumer demand. Idling plants, reducing shifts and slowing assembly lines are common approaches to lowering production.

In recent months, automakers such as Nissan, Stellantis and Volkswagen Group, have laid off autoworkers and idled or shuttered manufacturing plants to align production with market demand for their products.

However, OEMs with union workforces, including Ford Motor Co., General Motors, Stellantis and others represented by the United Auto Workers union, often pay higher costs to lower production, affecting when they lower production and by how much.

“The latest UAW contract has higher costs for long layoff periods, so that has to be factored in,” Brinley said.

The UAW also won the right to strike over plant closures during the most recent labor negotiations with the Detroit Three automakers, leading to a showdown between Stellantis and the union over the automaker’s plan to delay reopening its Belvedere Assembly Plant in Illinois amid weak EV demand.

Today’s vehicles may also share components and platforms, giving manufacturers more flexibility to adjust production based on market demand. Honda, for instance, builds the Civic and CRV at the same assembly plant and can adapt each model’s output to meet demand, Brinley said.

Additionally, while some automakers prefer to maintain lower inventories, some OEMs, such as Toyota Motor Corp., have been unable to produce enough vehicles. The Toyota and Lexus brands had 35 days’ supply in October, according to Cox Automotive.

It could be related to Toyota's just-in-time production system, which aims to limit excess inventory in normal markets, Jominy said.

“The more efficient you are, the harder it is to get back to those efficiencies [after the pandemic] because you don't have any buffer,” Jominy said. “It’s going to take them much longer to recover than some of the other automakers that had more slack in the system.”

Figuring out what to sell and where to sell it

Keating said that automakers need to understand what types of vehicles they sell and where they sell them, especially when it comes to EVs.

“It’s more important than ever to get a handle on the regionality of vehicle sales. If you send the wrong trim levels to the wrong places, you’ll need to incentivize them,” Keating said.

OEMs also need to target inventories that make sense for their dealers and customers on a per-model basis, Brinley said.

“That 60 to 80-day targeted supply is very, very much a fluid target,” Brinley said.

Some vehicles, such as full-size pickup trucks, require dealers to keep higher inventory levels because they come in several variations, leading some automakers, such as Ford Motor Co., to maintain higher overall inventories than those whose lineups have fewer build combinations, such as Hyundai. While full-size pickups have varying cab lengths and doors, other vehicles like subcompact SUVs often don't.

“If you strip supply down to 60-70 days of pickup trucks, you won’t have the truck that somebody needs available when they need it, and that gets to be a problem,” Brinley said.

The scale of the market matters, too, Brinley said. There are only six full-size pickups available in the U.S., giving each manufacturer a larger market share and requiring higher inventories. The subcompact SUV market, meanwhile, has a few dozen, which means smaller market shares, lower inventories and fewer build combinations.

It’s a “balancing act” for automakers, Brinley said. Automakers often have similar trim levels, such as LX or Platinum, across their vehicle lineups to ensure they meet customers’ needs. However, they may simplify the build combinations within those trim levels to lower costs.

Some automakers, such as Ford, Honda and Kia, are also introducing lower trim levels with less standard equipment to give consumers more affordable options rather than lower prices or rely on incentives to improve affordability.

However, while removing features from a trim level can help automakers lower costs, it can also backfire.

“If you take the wrong things out, consumers see it, and they don't like it,” Brinley said.